Why is reflective practice important in education?

This piece was written by Esther Cummins, educator and Course Leader of MA Education (Online)

Many years ago, I was a Brownie; for those who are unsure what this means, it is a form of Girlguiding in Britain – like Scouts. To become a fully-fledged Brownie, I took part in the ‘Brownie Promise’ ritual of standing next to a ‘pool of water’ (a piece of cardboard decorated with tin foil), and speaking the words, "Twist me and turn me and show me the elf, I looked in the water and there saw myself”.

The ’reflection’ that I saw in the pool is key to the Brownie story. Instead of seeing a helpful mythical creature, Brownies are taught that they can be better by taking responsibility for their own actions. This recollection may seem a strange way to start a piece on reflective practice; however, I have found through incidental conversations over the years that many people mistakenly view reflective practice as a form of navel-gazing that somehow inspires them to be better through guilt or revelation.

Reflective practice is not about staring deep into ourselves for answers, nor is it about ‘being good’. Reflective practice is not about an authority figure telling you to modify your actions and it is not a one-off exercise for personal improvement. So, what is reflective practice?

What is reflective practice?

Reflective practice can be broadly defined as the process of “learning through and from experience towards gaining new insights of self and practice” (Linda Finlay, 2008). Reflective practice started in the field of nursing and has developed into several guises; Finlay’s research shows that, “multiple and contradictory understandings of reflective practice can even be found within the same discipline” (Finlay, 2008). Across the models of reflective practice, Finley points to the following common aims:

- Learning through and from experience

- Gaining new insights

- Examining assumptions of everyday practice

- Self-awareness

- Critically evaluating one's own responses

- Life-long learning

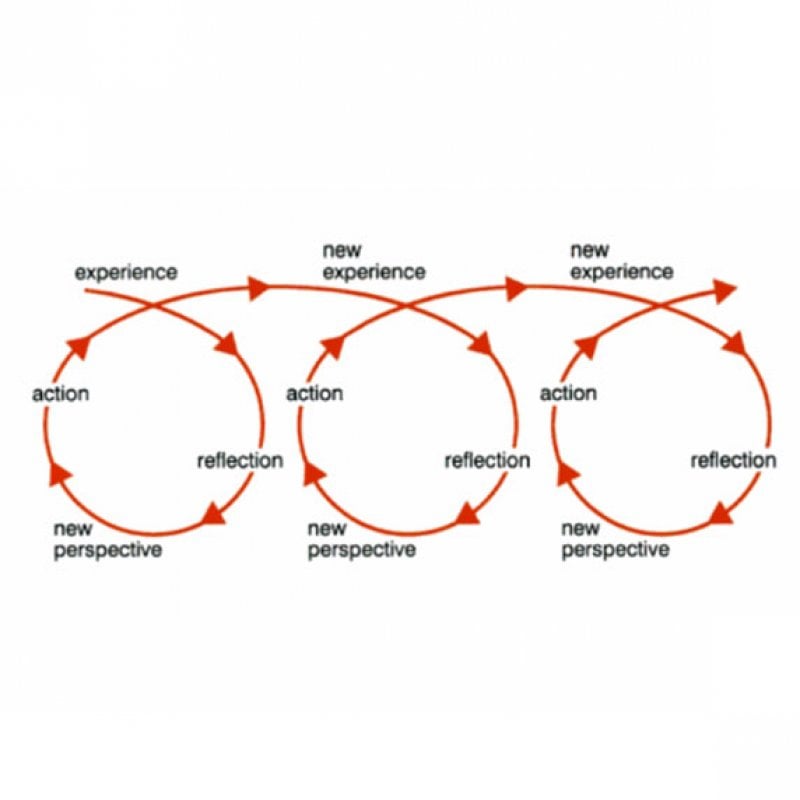

The various models of reflective practice (such as Gibbs, Kolb, Dewey, Driscoll, and Schön) each offer a process to support reflective thinking to learn from an experience. There is an emphasis on doing or taking action as part of the process; it is reflection for purpose. Melanie Jasper’s reflective practice model (Figure 1) shows us the cyclical nature of the process. She expands this thinking to show reflective practice as a spiral (Figure 2), an ongoing process that supports development and learning.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Throughout my career, I have tried to use reflective practice to develop my teaching. There have been many moments and experiences that I have chosen to reflect upon my own values, beliefs, and practices. One of the cyclical processes in my work has been related to the work of inclusivity within education. Below are three examples of where I have used reflective practice to develop my own thinking and pedagogy, with a particular focus on working with bilingual children (commonly referred to within the English education system as children with English as an additional language or EAL).

Reflective practice examples

Example A

An experience

As a newly qualified teacher, I had a child in my class who had recently moved to England from Nigeria. In a meeting with his mother, another professional assumed that the family had seen many safari animals, when they had in fact lived in a similar town to the one I taught in.

Reflective processes

I took the time to consider what went wrong, including a lack of insight and preparation while having assumed knowledge of the family’s circumstances. I then explored alternative scenarios such as asking the parents about the child’s background or doing personal research into the country and town.

Action

I decided to reach out to the parents of children who had recently moved to England and invited them to speak to the class as the experts on their own countries.

Example B

An experience

When I was studying for my MA, I wanted to learn about supporting children with English as an Additional Language (EAL). I researched the language we use, including Conteh’s model of English as an Additional Language, which looked at how reframing work with non-native speakers of English can move from a deficit perspective to an asset perspective.

Reflective processes

I researched why Conteh used the term ‘bilingual’ instead of EAL or multilingual. I considered what my experience of the terms had been.

Action

I began to use the term ‘bilingual children’ rather than ‘EAL children’ in assignments. I adopted the term for use in schools and then when teaching in HE, I explained to staff and students why I chose to use the term.

Example C

An experience

I heard the term ‘othering’ to describe people who were ‘outside’ of the accepted group of people. At a similar time, I began to understand the concept of unconscious bias.

Reflective processes

I considered my own classroom and leadership practice. I realised that aspects of my practice could unintentionally be considered ‘othering’. For example, a celebration display of languages spoken highlighted the differences without giving students opportunities to learn about the cultures.

Action

I included more natural ways to celebrate diversity in the classroom, including the use of resources such as books, home corner play items and visiting speakers. I also found opportunities for children and staff to learn phrases in different languages.

These three examples of reflective practice did not happen within a short time frame, nor did they happen in the same schools. In fact, they happened over several years. However, these examples demonstrate the possibility of improving one’s educational practice by reflecting on past experiences.

Whilst reflective practice has helped to improve my expertise in the field of education, Jasper’s cycle means that I continue to enhance my practice, going beyond the hope to ‘be better’ that I promised as a Brownie.

Falmouth’s MA Education (Online) teaches students how to engage with reflective practice to improve their own pedagogy. This master’s course is suited for anyone who sees themselves as a lifelong learner as well as an educator. Alongside a commitment to study, we ask for authenticity and vulnerability, as these traits allow true learning and development to happen. In return, our students will gather tools to improve their educational practice, not only in the short term but for the rest of their careers.

If you’d like to enhance your teaching expertise and become a more confident, creative and reflective practitioner, then join our online course in MA Education.