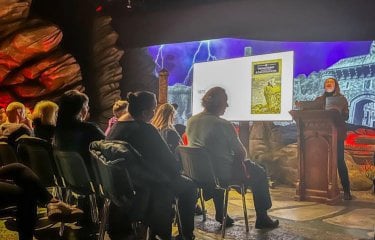

Stop Motion Tips from Head of Animation & VFX

26 June 2019

Before he joined our School of Film & Television, Andy Joule, Head of Animation & Visual Effects, was in the industry for nearly 20 years as both an animator and director.

His extensive experience includes work for studios such as Aardman Animations, Cosgrove Hall Films, Tony Kaye Films, Red Bee Media and HOT Animation. He’s worked on children’s programmes, title sequences, commercials and films, many of which have been nominated for – or won – awards. In 2007, his BBC animation - Kill It. Cook It. Eat It - was awarded a Yellow Pencil at D&AD, one of the most prestigious design competitions in the world.

Andy’s specialisms are stop motion animation and directing attention in VR.

Here are his top tips for producing a stop motion animation:

1. Story.

It’s got to have a good story, first and foremost. Without a good story, it’s just technique. It doesn’t have to be a unique story; you can adapt, appropriate, retell.

2. Understand film language.

As a director, you need to learn film language to be able to communicate effectively and tell your story. Animation takes a long time, so using film language can help you save time or use your time more effectively, investing your time in quality animation.

3. Practice.

Rehearse your shots. The more you can rehearse it the better, but try and maintain that spontaneity of performance.

4. Study acting.

Understand where the characters are coming from. Your puppets are actors; you are making them act. We don’t want to see puppets that are just moving around, anybody can do that. They’re actors and they are having an emotional response; they are capable of independent thought and they are autonomous.

5. Don't feel you have to throw lots of money at it.

It’s very easy to think you have to have all the latest and greatest bits of shiny kit – the ball and socket armatures, flashy cameras and stuff like that – but you can make puppets very simply out of plasticine and wire. Again, it comes down to the story. If the story is great, it can be a really shonky puppet, it doesn’t matter.

6. Be aware that it takes a lot of space.

You need a lot of space to make a stop motion animation, so if you’re doing it at home, set it up in your bedroom or garage or ask your parents to clear some space.

7. Make sure everything is glued down.

Make sure the lights are not going to move – if a camera gets kicked then quite often you have to start again on that shot. But it’s also amazing what you can get away with. As long as it looks good to the camera, what’s going on behind the scenes is a bit like when you walk onto a stage; from behind the scenes it’s just tat and bits of this glued and nailed, and things holding it together. Then you go on the other side and it’s magical. It’s the same for stop motion.

Dress it for the camera and it doesn’t matter how it’s held together behind it. I think that’s what most stop motion animators like, is that actually it’s just 99% improvising the whole time. You’ll get into a situation and think, ‘ah, puppet won’t stand up, but I’m halfway through a shot, what am I going to do?’, ‘I’ll put some pins in here and I’ll get a bit of fishing wire and I’ll hold it up and I’ll tape it to there’.

You’re constantly having to invent stuff.

8. Have an interest in performance.

Go to the theatre – I say that for all animators – watch theatrical performance rather than film performance. Ballet; watch how it communicates. I always say, don’t study film acting for animation because it’s different. In a theatre, you can be 150ft away from an actor; if they’re trying to convey they’re upset, it has to be more physical.

It’s a much more physical performance for animation; it’s almost a little bit like pantomime, certainly for cartoon, as it’s a much more exaggerated form of theatre acting. Go and work in a theatre for a bit and watch ballet.

9. Demystify sound.

Don’t be afraid of sound; too many visual people get to sound and say, ‘I don’t really know about sound’, without thinking – you have two ears, you hear stuff all the time, you watch films and TV, cinema, theatre… sound’s being used there.

Too many people let it wash over, rather than taking time to analyse how you can use sound to be your friend and actually let it do a lot of the work for you. For example, if you’re running out of time and you’ve got a character that’s doing a lot of talking, have them go out the room and carry on talking, then come back in again.

10. Avoid dialogue.

Lip syncing takes a lot of time. All dialogue is broken down frame-by-frame, so the animator can then manipulate the mouth to the right shape, particularly ‘m’, ‘b’, ‘p’ – anything with the mouth closed – because if you miss those, it really shows. You need to be able to see it at a glance. The vowel or the letter needs to be right and that’s really time-consuming, particularly if you’ve sculpted it in clay.

Anything that avoids all that… for example, Gromit doesn’t say a word, all he does is lift his eyebrows. And actually, lip sync isn’t just the mouth moving, we’re drawn to the eyes rather than the mouth. It’s the eyes that are communicating; when lip syncing, think about what the eyes and the eyebrows are doing.

11. Be a people watcher.

Develop a library of idiosyncrasies, so that you can just go ‘ah, I’ve got this character and there was this person on the bus that was doing something nobody else has ever done before’, then build that into a performance. You do have to think a little bit like that; borrowing things from people.

As an animator, you’re watching them, but you’re not just analysing how they move, you’re thinking, ‘okay well, they’ve got an odd walk, what is it about that walk, it’s a slight limp’, so that leg’s going on a twelve-frame cycle and that leg’s doing a sixteen-frame. Then you’re starting to think in terms of frames. It’s a bit weird.

Just look, keep your eyes open, put your phone down, be really observant. There’s a whole world out there; watch people and be curious.